Monitors

I told Neil that I didn’t like turn-based stuff. I like RPGs a lot-- games like Diablo are the shit-- and I don’t fault anyone who likes their Final Fantasy or Tales, and I’m not even saying it’s bad game design. I just don’t like them. Some people like cinnamon. I think it tastes like dirt that’s on fire. It’s just a matter of preference.

When Neil pushed it further, I said I also didn’t like the whole player-created-content idea. I don’t want some idiot asshole somewhere making their shitty OC RPG dreams a reality; I want carefully made content by creative people, or at least a well-executed roguelike. Do you know how many of those levels in those game-maker games are just re-creations of other games or, even worse, auto-playing levels that don’t let the player do anything? I asked this of Neil. He nodded and acquiesced my con list. He kept right on pitching.

Neil is a genius, and his genius is my weakness. If he’s got an idea, odds are that it’s good. I let him pitch URPG to me, and by the time the pitch was done, I was convinced to make a prototype. And by the time I was done playing through the prototype and I scratched out a few notes of my own, I was convinced that Neil and I had something special. The whole JRPG-style thing still wasn’t my flavor, but what Neil had shown me was something people would truly love, something that a lot of people had been thirsty for. We Kickstartered URPG using Neil’s prototype, and it was funded in less than a day. We quickly made stretch goals – multiple graphics styles, extra customization options, personalized items in the game for the high-rolling donors—all funded in hours of going live on the site. Neil brought me some excellent artists and programmers to hire, and we started our studio, “Days of Fire.” It was my name.

Everyone except for me was so damn talented that I felt like I was just holding them back, but Neil said I was a leader and an organizer, a skill that nobody there had. If not for me, Neil said, they would have run out of money in a month because nobody else there understood finances. I countered that I was a good big picture person, not a leader, that maybe it was better to call me a “manager.” That seemed to satisfy both of us. It seemed to be an interesting angle for all the video game publications, too. People responded well to a figurehead that was really a behind-the-scenes person. I talked like a fan instead of a creator. I talked like someone who loved a game they should hate, and that ended up being the best sales pitch.

Launch day was low-key for us. URPG had been in beta for a while, so there were a few moderately well-done creations, (URPG calls them “Arpeegees,” which was my one great, cute idea) but for the most part the Arpeegees were rushed messes that people had cranked out in the few hours since the full release went live. I hung out with Neil on his couch while he played awful things by awful people on the big wall-mounted monitor. The rest of the dev team hung around our offices, too, with their laptops on the Wi-Fi, laughing through pizza-stuffed mouths at all the ridiculous things people made. The game’s customization tools were impressive and somebody probably could have made a pretty great Arpeegee if they tried or had any talent, but nobody ever did. Maybe they would have if they’d had the chance.

I watched him play one for a few seconds that seemed to be just NPCs spewing slurs. I wanted to put that one in the ground, but I didn’t say anything. Neil still picked up on it, though. He knew me well.

“Should I ban that one?” he asked, doing well to keep any implication out of his tone.

“I mean… it’s the first day,” I said delicately. “We should probably at least get rid of anything that’s intentionally offensive.”

Neil didn’t say anything, but he did turn to his laptop, typed in an ID number, and then deleted a line from a list on his screen.

“Done,” he said, flatly.

“I know how you feel about that,” I said.

“I guess,” he said. “I’m not really crying over censoring racism for racism’s sake, though. Plus, it’s the first day.”

“It’s the first day,” I repeated.

“And you’ll have to be the one that explains why we’re censoring,” he said with a smirk.

“’cause it’s our fuckin’ game and we can fuckin’ do what we want!” I said loud enough for the whole office to hear. I got a hoots and woos in return, Neil included. “It’s our fuckin’ game!” had become our catchphrase, a thing we yelled when we were tired and needed a morale boost. Now it was a victory cry.

“Besides, it’s not like we’re cutting stuff out en masse,” Neil said, still justifying to himself and pronouncing the French with a heavy American accent. “We don’t have the filtration algorithms that Super Mario Maker has. How many of these things are just dicks?”

“So many dicks!” I yelled, laughing until tears came. “Towns shaped like dicks, NPCs huddled into dick-shaped crowds! Look, I’m pretty sure your sword is tweaked to be even more dick-shaped than swords already are! See? See? There’s little balls at the bottom of the hilt!”

“Okay, one more,” Neil said, almost pleading with me.

“Hey, you play as many as you want, bro,” I said, leaning back and putting my feet up to rest from my laughing fit. “I’m having a great time.”

He thumbed over the d-pad on his controller until the Random button was highlighted. He tapped the “A” button and the Random Number Generator crunched numbers to decide which Dicktropolis to save next.

For a little while, maybe a week, I was so excited to have been a part of what happened then. Excited that I was project manager/editor/CFO/whatever of the Thing That Made History. Obviously, I’m not so excited now.

“That’s… weird,” Neil said after the loading bar was finished doing its duty. It was weird. URPG was capable of making games in three visual styles: A classic pixelated top-down 2D style, a PlayStation-esque style with 3D characters on 2D backdrops (this was the rarest kind, probably because it was the hardest to make since it required you to upload your own images to use as backdrops. The few levels I saw were usually photographs with poorly-placed paths for the characters to walk on), and full 3D games using pre-existing assets that creators could tweak some. What appeared on the monitor seemed to be real, live video. Like, from a camera.

“Can people upload video?” I asked. “They can’t, right?”

“Is it video?” Neil said, squinting at the screen.

It was hard to keep up with it. Now it looked rendered, but in much more detail than the game should have been able to muster, and with assets the game shouldn’t have had. It felt like my brain couldn’t ever quite settle on which it was—full-motion video or game graphics.

The Arpeegee was in first-person, too, which URPG doesn’t have tools for. I think, at first, I just assumed somebody had found a way to finagle the game so that it just seemed like it was in first-person, like the actual player avatar was somewhere out of sight. I’d found a level like that in Little Big Planet when I was doing research for URPG.

The scene looked like a regular house, like one I could buy anywhere in Montreal. The camera was in a nice kitchen, an upper-middle class kitchen. There wasn’t anything strange about it except for the headache-inducing view. It was clean, attractive, and homey. Like it was in a magazine.

“Hit the stick,” I said. “Does it do anything?”

Neil tilted the left control stick on his controller forward. The point-of-view moved forward a few steps. The “head” bobbed, another thing that should have been impossible in URPG.

“Can you explore a little?” I said, daring to take my eyes off the screen to turn toward Neil. Neil kept his eyes glued forward.

“Yeah,” he said quietly. He was always quiet, even in the face of weirdness. A quiet genius. He swiveled the right stick around tentatively, and the POV looked around the kitchen. He turned hard 180 degrees and saw a living room just as nice as the kitchen. There was a huge television screen mounted on the stone wall above an unlit fireplace. He moved toward it. The TV showed the lobby menu for URPG. The Random button was highlighted.

“No way,” I said, almost whispering. “That’s not possible, right?”

“Maybe,” Neil said. “I guess if they used some kind of virtual machine.”

“But, they’d have to hack us to be able to do that, right?” I said.

“They wouldn’t have to hack the servers, but they would have to mod the game pretty heavily,” Neil said. Then, after a moment, “I wouldn’t call it hacking.”

“Shut it down, anyway,” I said. “Just in case.”

“First day, right?” Neil said.

“First day,” I said.

Neil brought the ban hammer down again. We were back in the lobby. The Random button was highlighted.

“Do it again,” I said. “Let’s just make sure that was a weird fluke.”

A 2D pixel art game came up. Two characters stood in the center of the screen in what looked like a hallway with lockers. There were other characters standing in the hall, but the two in the middle seemed to be the focus. The characters both looked feminine, but it was hard to make a judgement on that for sure. Maybe they were supposed to be neither— I’d seen plenty of people use pixel art to make non-binary characters a la Undertale. It was just one screen, but it was impressively well put-together. The 2D games were tile-based, so people could make their own tiles by just manipulating pixels on a 20 x 20 pixel grid. It was an easy-to-use tool, but it was time-consuming. Almost everything on this screen looked like it was custom-made.

“It’s still got that modern look, like the last one,” Neil said skeptically.

“Yeah, but maybe it’s going for, like, an Earthbound or Persona thing,” I said.

Neil chuckled, breaking the stress in the air. “Oh, two games you hate,” he said.

“I don’t hate them!” I said, a little defensively, if I’m being honest. “As a matter of fact, I might actually appreciate them a little more since I had to play them all and they’re—“

I stopped. The TV had caught my eye. The graphics were doing the strange blurring between facsimile and reality, but the pixel graphics made the line between the two much more clear. I watched the locker flicker between pixel art to photorealism and then to another pixel art rendering of a locker, as if the game had several looks to choose from and couldn’t decide on one. Neither Neil nor I spoke. Some of the other team members had noticed we were acting strangely and had come to see why.

“Why is it doing that?” said Raven, our in-house pixel artist who had done all the pre-loaded pixel art and helped create the tile editor.

“Should it be doing that?” I asked. “That’s not a feature, right?”

“Not that I know of,” she said. “Maybe it should be!”

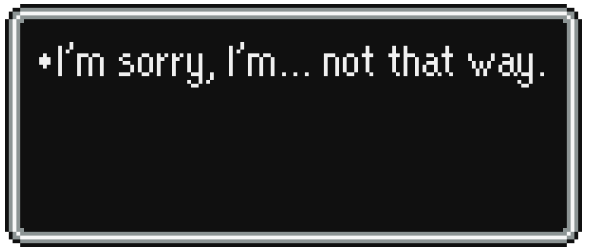

A pixelated dialogue box came on screen. I shushed everyone, which was unnecessary because the game didn’t have any spoken dialog options, yet, only text. White text typed out in the box, accompanied by beeping sounds.

The dialog disappeared and one character exited the screen quickly with a two-frame walking animation. The other character seemed to collapse to the ground in despair. The screen darkened until that character was alone on a black background.

“Back out,” I said. “Do another one.” He did.

We did this for days. Every Arpeegee was different, but they all had the same tones. Modern, realistic settings. Barely any gameplay. Dreamy fluctuations between photorealism and video game graphics. Short vignettes of people’s lives; some were sad, some were funny, some were mundane. We found a few “real” Arpeegees here and there, the shitty ones that had shown up in the first few hours on launch day, but they became rarer and rarer.

Video game news was fascinated by the phenomenon. They all seemed satisfied with our lie that the community had just embraced making short, avant-garde games using URPG’s tools. Kotaku even had a weekly roundup where they spotlighted a few they liked the best. We all decided it was best if I stuck to that line in interviews until the rest of the team had figured out what was actually going on. I realize now that I always knew. Maybe we all did.

One day, a month after launch, we got this report from a user named Rextanimus:

I’ve sent a bunch of reports to you guys about my games not showing up, and now I have one in my account that I didn’t make. I think somebody hacked me? I need you to look into this ASAP because I’m getting kind of scared. The game is about me and they know some things I’ve never told anybody. Can you guys figure out the I.P. address of the person who made it so I can know if it’s somebody I know pulling a prank on me? I also can’t delete the game. Can you please, please delete it for me? It’s got some really personal stuff in it!!!!

“Is it a prank?” Neil said unconvincingly.

“It’s not a prank.” I said, the stress knot tightening in my stomach.

We were able to delete it, but it did require Neil to do some high-level system administrator stuff. I’d never seen him so confused or frustrated by a technical problem.

“I mean, lots of weird problems came up during development, right?” I said while standing in the server room. Neil’s back was to me. He was holding a laptop awkwardly in one arm and touching the mousepad with the other. He was looking at the blinking lights of one of the server towers. I wasn’t sure why exactly we needed to be physically in the server room, but I trusted Neil’s knowledge.

“This isn’t like that,” he said. “That was like… making a fancy dinner using a complicated recipe. This is like I’m making a sandwich and I can’t put the top piece of bread on it.”

“What are you gonna do?” I said. Neil’s back was to me, but I could see him bite his lip.

“If we want to delete that one user’s one game, we have to wipe this whole tower,” he said, knowing that I would not like that.

“Can’t we back it up?”

Neil shook his head. “I don’t want to do that. The players probably still have their levels saved on their local machines. They can just upload them again.”

“Their stats will be gone, though. All the plays and faves will be reset to zero,” I said. Neil didn’t say anything back, but I knew he wouldn’t. The stats actually hadn’t been working right for a while, but we didn’t talk about that. We weren’t talking about a lot of things.

More reports with the same story appeared in the next few weeks. Other user reports said their Arpeegees they had uploaded had been played zero times, but the false ones attributed to them that knew their private thoughts sometimes had hundreds of thousands of plays. Video game news got wind of it pretty quick. I must have sounded like I had something to hide when I told Kotaku and Polygon that I didn’t know what was happening, but it was the truth. All I had were stressful feelings in my stomach. I didn’t have facts.

Mainstream news picked up on us about the time all the “real” Arpeegees disappeared entirely. I told them the same thing I told Kotaku. The fearmongering think pieces started at about the time the full-motion-video Arpeegees of people’s thoughts started showing up. Politicians started talking at about the time the game reached a billion downloads. The protests started when the Arpeegees started showing people’s full names and addresses.

Finally, law enforcement stepped in. I think that was the beginning of the end. I bet a lot of people think that way. The most-viewed Arpeegee on the server at the time was a full-video one where a person—it’s in first person, but it’s obviously a guy-- walks up the stairs of their apartment, knocks open the door with a sledgehammer, and screams “You! Are the worst neighbors! I’ve ever had!” at a family cowering in their living room. One of the moms sobs apologies in a way that would be satisfying for a person having a revenge fantasy. Without acknowledging the apology, the man takes his sledgehammer to her face. It caves in. There’s no blood, she’s just dead with a black crater in her face. The hammer goes into the other mom’s chest, indenting it. It would be satisfying if it wasn’t so real, I admit. If it had been a Nazi from Wolfenstein. The guy screams “You can’t vacuum at 2 a.m. if somebody lives below you!” He moves onto the kids, screeching more complaints as he murders them. Police found a guy in Texas with the name and address displayed on the screen who lived in an apartment that looked like the one in the Arpeegee. He was arrested and convicted on Conspiracy to Commit Murder. His neighbors were fine. They said they’d never even spoken to each other. They even had a third kid the guy had never met.

Riots happen almost every day in almost every city in the world that’s connected to the Internet. The only places where there’s peace are the countries that censor their Internet. I’ll admit to a little marveling at that irony. I don’t know who was right and who was wrong anymore.

The team hasn’t been in the office for weeks, except for Neil. One night Neil left to go home at 2 a.m., and I went to a 24-hour grocery store and bought three cartloads of mostly non-perishable food. I carried it all into the office, nailed every door and window shut, and moved my favorite chair into the server room. I breathed full, deep breaths as I watched the lights blink on and off and listened to the fans. I tried to enjoy the crisp air-conditioning on my face. Nobody but the dev team knows where the office is. I figured I could hole up here for months at a time. We own the space. The water and power companies don’t know us, they just sent us a bill like anyone else.

Neil’s mighty hands slammed on the door later that night. He tried once to barge through it, I think, before his usual calm self took back over and called my name. I talked to him through the door.

“Hey, Neil,” I said.

“I had a bad feeling,” Neil said, answering a question I didn’t ask. “Was it right?”

“They’re going to make us take the servers down,” I said. “Well, they’re going to try.”

“Who?” said Neil. “The police? There’s no warrant.”

“I think this has gone beyond people going through proper channels,” I said. “It’s not civilized anymore.”

“So, you’re just, what, embracing anarchy, now?” Neil said, an anger I had never heard sneaking into his tone. “Shouldn’t we stop this now while we still have control of the situation?”

“No,” I said flatly. I had known Neil long enough to not have to explain beyond that.

“This is wrong,” said Neil. “You are doing the wrong thing. For god sakes, I’m on your goddamn side for once, and now you refuse to shut this down? Now that it’s actually dangerous?”

“That’s my line,” I said. “Aren’t you happy? You’re the one who convinced me. It’s not our fault it can see inside everyone’s heads,” I said.

“It doesn’t matter whose fault it is,” Neil said. “Everyone outside this door wants this to end.”

“The game’s been downloaded 5 billion times,” I said. “That’s well over half of the people in the entire world, Neil, and the number keeps climbing. Two billion people are playing right now. If they want it to stop, they’ll uninstall it. They’ll stop playing.”

There was silence from the other side of the heavy metal door. At first I thought he had left.

“Be safe,” he said calmly, but strongly. “I’m leaving the country. I won’t ever talk to you again.”

Tears flooded the bottom of my eyes. I didn’t say anything back.

I put a copy of the game on almost every monitor in the office. I guess I’m just torturing myself now. Two days ago, I watched a mob shoot Raven in the head on TV. Not on the game, on the news.

Yesterday, I unplugged the servers.

Today, 4 billion people are still playing the game. I think I knew that would happen. Even when they were powered on, there was no way the servers could have even handled even just a billion people playing.

I smell burning outside. I’m safe, though. The player is always safe when they’re playing a game. It’s the people in the monitors who get hurt.

Benjamin Gray

Benjamin Gray