Chapter 5

Waters was annoyed. He’d entered the circle with only his usual, cursory nod at the two women, but had received no welcome from either: not usual for either of them. He took his time at his own chair, settling his belongings about it on the ground, hanging his bag from its back, and rigging his shade fly, to allow them ample opportunity, but they did not afford themselves. Finally, he settled into the seat with a sigh built little from content with his return to his firecircle and much from the exhaustion of dealing with events – and the Umbriel - these last hours. His foul mood remained, and the silence and poorly feigned non-interest of the women was doing little to correct it.

Ndhima was obviously trying to catch Willow’s eye, but Willow was having none of it, working hard at ironing her skirt to her thighs, cleaning her nails, and picking at non-existent lint. And paying very close attention to each task. Ndhima was no better, though, stirring the soup and stirring the soup and stirring the soup as she was.

Well, let them suffer for news, if they weren’t willing to ask, he thought. He was sure they’d heard by now. After all, the rumor had reached the encampment before he did (much to his surprise, if he let himself think about it) and he knew these two would want to know particulars. They always had before, and had no trouble pressing him for it, usually. But not this time. If they wished a self-given, effusive recounting, they would sleep still wishing.

Still, it would be nice to vent a bit, he thought, and the women of his camp had always been good sounding boards. The Umbriel’s short-sighted apathy still stung. How could the crone deny him the quest? The host’s assistance? It was the right thing to do. Before the light found another. Yes, he would like very much to vent. And to share his sorrow. It was such a burden when carried alone. Much like a secret.

The old man shifted in his chair, fatigue making even his clothes seem heavy against his skin. He looked over to the nearest neighbors’ firecircle. They, too, were busy trying to ignore him. He watched the top of Willow’s head as she picked at the fabric of her skirt. He watched Ndhima still bent, still stirring. He could understand his neighbors’ reaction. They tried most times to avert their eyes, anyway, whether out of fear or deference, he didn’t care, but these two had never treated him with such kid gloves. Even at his worst, Ndhima had always managed to match the barbs from his tongue. He sighed again, more frustration than exhaustion.

“Keep stirring like that, Ndhima, and all the vegetables will mush.”

The poor-witch startled, quickly set the spoon aside and moved to busy herself at the sideboard, almost forgetting her staff by the fire in her haste, Waters noticed. So unlike her. The bells at her ankles jangled as more proof of her discomfiture. Ndhima’s bells normally rang true with each step, a rhythmic melody singing her poise and confidence. A jangle at her ankle was the same as a jangled nerve for her. Perhaps she was feeling the guilt of her last encounter with the girl. That must be it. And the same for Willow. He watched his oldest friend remain intent on picking at the weave in her lap, her hands shaking with each movement. Was the tremor more than usual? Guilt for her role, too?

“Need you new fabric for a skirt, Willow?”

The ancient woman’s hands flew up like birds and quickly moved to smooth the skirt across her thighs. “No. No, thank you, Malakamawti. This skirt is just fine,” she whispered and continued to iron it across her lap, never raising her head.

“Malakamawti?” he countered. “Since when do you use my title? And especially at our fire?”

She quickly corrected herself: “No, thank you, Waters,” and glanced in his direction, but did not meet his eyes. The silence fell again. Willow would not be the one. Ndhima, then.

“Is it pullet, Ndhima? Are there dumplings?” he asked, hoping to have even a small response, wishing for some sense of normalcy around his campfire.

“No dumplings,” the witch countered without looking up. “We still have bread from last night.” Silence fell again.

“Is it nearly ready?” Waters asked, knowing the answer by the smell, but wishing again to hear a voice.

Ndhima snatched up the stack of bowls from the sideboard with a clack and clatter, threatening to dump them to the sand, causing Waters to nearly jump from his chair to assist, but she quickly grabbed at them and fixed their balance. Then she squared her shoulders and took a deep breath before turning around.

“I think…” she announced as she returned to the fire and the pot, her skirts swishing in harmony to the chimes from her ankles. Something had changed. Just then. Something had changed. “…the vegetables are sufficiently mushed.” She took up the ladle and offered him a sheepish smile.

He returned it, to ease her. “Well, mushed or no, I am easy to please. I am starving!”

“Did not the Umbriel feed you this day?” the witch asked, approaching with the full bowl, steaming even in the desert heat. He shook his head no as he carefully took it from her.

“There was much to discuss.”

“So it is true.” At last, thought Waters. He knew he could count on Ndhima.

“Yes, dear. It is true.”

“She fell from the sky?” Willow asked. And the damn had broken. They would ask now, and he could relieve himself of some of his own pain. Oddly, he found it hard to answer, his throat suddenly tight and his eyes stinging. He could only nod and swallow, the bowl set aside on his camp table. “Are you sure it was her? What was she doing up there?” she continued, leaning in toward her friend.

“That’s where she lived, Willow. In the clouds. And for giving you that lie, I am truly sorry.” Waters offered a hand which she took with a small squeeze and a small, forgiving smile.

“There is much for which we are all sorry,” added Ndhima, now knelt beside Waters’ chair. He caught her eyes and felt the comfort there.

“And it was her. I saw her. Lying there. All--” He could not continue the description.

“Oh, Waters.” Ndhima squeezed his arm.

#############

“Don’t be sorry, Rebekka. What do you have to be sorry for? Are you kidding? No. We’ll work it out. It’ll work. I know it.”

“Perhaps we should just forget the Emotive. We have—“

“No! Not for her.” Ibe caught himself. Right now, Rebekka needed to brainstorm, and his emotions were running away with him. He began again with a staid, science voice. “I think that, given the nature of the information in the overTracts, the new string is essential to gaining a complete picture for… this subject.” She smiled at that. Knew what he was trying to do. “We know it works,” he continued. “We just have to figure out why it isn’t working right now.”

“It works in theory, Ibe. Just theory. Controlled experiments. Simulations. I’ve never run it on a human subject. I’ve never tried a practical application. And Davidson is going to want a report soon.”

“The report on even what we have is going to take ages. I don’t want to waste precious Cryo time working on a report. We need to figure this out first.”

“If I had time to Tract multiple subjects, compare the data sets, it might show what’s wrong with it.”

“It’s not wrong.”

“Well, it’s not right!” she yelled. Rebekka looked close to tears as she flung her arms toward the ceiling, but he knew it was just her exasperation raising her voice in pitch and decibel.

“Maybe the Tract is flawed,” he offered.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” she barked, then caught herself and he watched her consciously calm herself. “I mean, how could it be?” she rephrased, and picked up the handheld, all the same, to look over the code. “It’s still Party Dip. All we did was attach the string.”

He smiled at that. Their little inside joke. She’d been incensed when Ibe told her what Davidson thought of the name, but she’d quickly recovered, given the overall good news surrounding that minor slight. And then they’d made love. He could have lain with her all night then, tracing the lines of her naked body in the moonlight from the display window. But there’d been work to do. Lots of work. And he’d wasted enough time going home in the first place, since he couldn’t trust this news over the phones. Phones had Ears, more often than not. In truth, he’d felt a bit guilty about the love-making, too, thinking it was more time than they could spare, but only a little bit.

And then his guilt had slipped away as he’d marveled at the workings of a mind that could outdistance his Regulator Cryo by megameters, in the time it would take most people to merely concoct a useable hypothesis. If the Regulators’ Cryo goal was Level 4, her working settings were Level 100. He would never even have conceived of being able to keep a subject viable for a week. A whole week!

She’d given him the settings so he could adjust his own lab, and he’d agreed, even though it wasn’t sanctioned. Then he’d taken himself off shift rotation. Now he had time to help her. This was more important, after all. This was the only important thing, honestly.

And to watch her again as she prepared for the Tract, the calculations flashing behind her eyes, even as she figured them on paper and slide before allowing the computer to make its effort (never could be too cautious), he’d found his joy again. And he’d laughed out loud when she’d embraced Davidson’s slight and used the name ‘Party Dip’ instead.

And then the data from that first Tract had come in and Ibe had been, well, awed wasn’t even a strong enough word. He’d known Overlay was heads and shoulders above anything ToD could do, from image and audio clarity to depth of scan. He’d helped her lay the foundations of it before he’d taken the position in Practical Processing (and his intellectual life had ground to a halt). But Party Dip had gone deeper than Ibe ever imagined Processing could. And effortlessly, like she’d said. He thought she was boasting at the time, but she wasn’t. God in Heaven, she wasn’t. He should have known. It was her real baby, after all, the Process. He should have known that Party Dip would be stratospheric in comparison to ToD. In comparison to Overlay, honestly.

He could not have imagined re-Tracting a subject more than three times - usually only two - with ToD, and with diminishing returns, each time, but in the last twelve hours, they had re-Tracted six? No. Seven times, now. With no discernable loss of data, let alone quality. For specific themes, for God’s sake. And going back years to find them. Years! His wife was the smartest person he’d ever known. Or even read of, for that matter.

“Of course, the Tract is fine,” she announced, setting the handheld down. “It’s obviously the new string. But I just don’t know. I really don’t. The progression is off, somehow. I’m missing something.”

“The theory is sound. It’s probably a misspelled word in the code or something.”

“It’s not syntax. It’s the whole idea.”

“It’s not the whole idea. Maybe it’s a misplaced line. From the splice.” She opened her mouth to protest and he quickly moved on. “Tell you what: we take the time to Tract others. I have other subjects in my lab with Firsts. We--”

“I don’t want her,” she blurted. As soon as it was out, Ibe saw the shock in her eyes at having said it. He was shocked too, but hoped he’d managed to control it before it wrote his face.

“There are others,” he assured. She blushed and turned her head. Both of them, it seemed, were having a hard time of it. “I still have the two from the Market.” The barest nod - her hair waving - was her response. He gave her a moment to collect herself. “I’ll bring them over.”

“Davidson didn’t give--”

“Rebekka. Do you honestly think I could ever Tract with ToD again? After seeing all this?”

“But the Board.”

“Screw the Board.” Now it was her turn to glance around nervously, and he had just a moment’s worry that she hadn’t swept, but then her grin told him otherwise, and he relaxed. “Do you want the raw data? Or shall we convert?” She sighed and fixed her spine before moving to the station and swiping at the slate. He suddenly noticed how tired she looked. Very tired. “Have you Revived?”

“What? No. I’m fine, really.”

“Rebekka,” he admonished. “We’ve been at this for how many hours? Even your brain needs recovery. I’ve got a whole case in my lab, I’ll just-"

“No!” She said it too quickly. She tried to play it off. “I don’t want it. We talked about this, Ibe. I want to keep all that stuff out of my system, in case…” her voice trailed off.

“But this is… What if you do it just for now and we’ll find you a cleanse after?”

“No! I don’t trust the cleanses either.” Something was up. He couldn’t figure it out, and she wasn’t going to tell him, obviously.

“Then you’ll have to do it the old fashioned way.”

“Like we have time for that.”

“I can run the Tracts. You hit your cot. I’ll wake you when they’re complete.” She thought about it. He could almost see the calculations rolling through her.

“Yeah. Okay. But let me set it up first.” She didn’t trust him with it, but he didn’t trust himself, honestly, so he couldn’t be mad about it. “And we’ll convert. But I’ll pulse a drop of the raw data before it switches. I’d like to see if there are differences there.”

“You think it might be the conversion?”

“I think it’s my new string, but I want to rule out all other possibilities.”

“You’ll find it. And it won’t be your string.”

#############

New light. Drawn. Pulled. Seeking, found. New whole. Not whole. Just light. Just she. New she.

#############

The door display read “Theater 1202.” Rebekka checked her wrist: 0758. She was late. Well, actually, she was right on time, but she always preferred to get to class a little early, if only to set up her slate. This was an outlier, though. Not only was it not her class, she’d decided to take it at the last minute, too, when Ibe had woke her - after only 2 hours - with the news that he had to leave and she’d need to finish the Tracts. He’d forgotten about this lecture, and it was one of the few that couldn’t – shouldn’t - be led by a TA. He was in the middle of Tracting the wife from the market, hadn’t even run the Emotive yet, and still had the tourist to do. She’d offered to take the class for him, instead, since honestly, leading a Q&C for an undergrad class would be easier on her sleepy brain than running Tracts.

The door opened and she stepped in, scanning the seats to her left. Only 50 or so people – it was an 8am class after all - were still finding stations, stowing bags, molding seats, docking held or syncing bedded slates, sifting to and opening books, and all of it accompanied by the chatter of multiple conversations and the noise produced by the aforementioned settling. Though she preferred these theater-like classrooms, it seemed a waste for such a small group, and it spread them out too much for her tastes. She always made her students fill the closest stations first. It was bothersome to have 2 people in the back on the right and 3 people in the back on the left of a room that sat 300.

“If you could all move down a little closer, please? Thanks!” she announced as she approached the podium. For its part, it recognized her and asked which of her classes – and therefore lectures - should be loaded. “Not this morning, Podium,” she replied and placed Ibe’s sliver against the obs, “I’ll need Ibrahim Heinemann’s lecture notes for week 9.”

“Authentication is required,” it replied. The appropriate spool appeared on her slate. Rebekka tapped it and typed the accesses as she continued to speak to the class.

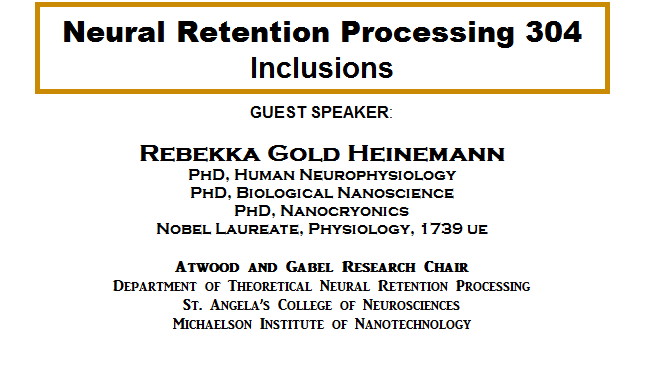

“Dr. Heinemann is currently tied up with a case, so rather than waste your time and run a lecture string you could easily have accessed elsewhere, and rob you of what I think is one of the better parts of our syllabi, I have volunteered to lead this class for him. There’s a lot of information to get through this morning, so if you could move quickly and…” Then she noticed all the sound was gone. She looked up. Students were frozen in place, as if time itself had somehow paused. Some were staring at her. Some were staring at the main display behind her. Some were looking back and forth between the two. It was the only movement in the room. She looked over her shoulder.

Thank you Podium, she thought, for scaring the shit out of these kids. She absolutely hated that litany of ’look how big my brain is’ podiums all over Urb automatically provided for her whenever she got near them. She’d told her own podium not to do it long ago, and so hadn’t even thought about the one in this new classroom.“Podium,” she whispered.

Thank you Podium, she thought, for scaring the shit out of these kids. She absolutely hated that litany of ’look how big my brain is’ podiums all over Urb automatically provided for her whenever she got near them. She’d told her own podium not to do it long ago, and so hadn’t even thought about the one in this new classroom.“Podium,” she whispered.

“Yes, Dr. Heinemann?” it whispered back. She nearly chuckled out loud to think the podium was conspiring with her.

“Remove my credentials from the display.”

“Yes, Dr. Heinemann.” She was erased. She turned back to the audience. The kids still appeared stuck in a processing loop, some halfway in – or out, she couldn’t tell – of their seats, some halfway down the aisles, some in mid-whatever they were doing to get settled, all with their mouths hanging open. Except for that guy standing on the right over there with his arm up, no doubt pixing for a sync to his soc later. Or even currently.

“Guys, please. I know this was not what you thought your morning would bring, but here it is. For my part, it’s been many years since I taught an undergrad class, so this is kind of new and weird for me, too. Let’s just settle in and get through this, okay?” A few of them slowly seemed to find themselves, and begin moving. “And I promise to speak – briefly! – to anyone who so wishes at the end of class. But only if there’s time.” That got them going. The settling rituals began in earnest, albeit without the usual susurrations of conversation.

“Right.” She gave them all a moment to at least find a station, then dove in. “Dr. Heinemann tells me you took your Seconds last week, so today is Q&C regarding the info in section 5, yes? So who has a question or concern?” No one answered. Of course, no answered, Rebekka, she thought to herself. Most of them must have a lump the size of a… Is that our neighbor, Oliver Wainmere?

A young man in the third row was slumped behind his display, trying very hard not to be seen. That trying was, in fact, what had brought attention to him. “Mr. Wainmere?” Rebekka asked. The man looked up. “I thought that was you. Do you have any questions or concerns about what you read in Section 5?”

Oliver shimmied up to a fully seated position. “The math concepts were a bit hard to get through, but I think I figured them, thank you, Dr. Heinemann.”

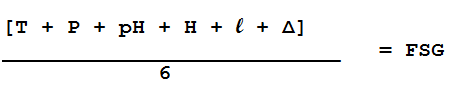

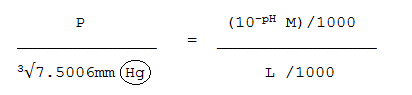

“Ah yes. The maths.” Thank God – and Oliver - for an opening, however small. “Let’s look at the maths, then…” Rebekka took up the pen, swiped her hand across the slate in the podium and began writing out several intricate equations. They appeared on the main display.

“Who can tell me what this equation finds?” No answer, still. “Come now. If you all ‘figured them’ as Mr. Wainmere has, then this is an easy way to get your participation score for the class.” Rebekka scanned the faces in the theater, illuminated by the glow of their displays. Some were staring fixedly at that display, but others were staring at her, then immediately at their display when her eyes fell on them. “Alright.” She tapped a pin on her slate and the real-time seating chart appeared. She picked a name at random. “Ms. Broward. What does this progression find?”

“The Combined Found State Grade,” said a young lady on the far left of the room.

“Yes! Very good. And you there, to her right,” Rebecca checked the chart, “Ms. Clamborg. What do the variables in this progression represent?” Rebekka checked her slate again, “Well, this should be easy since you tested so very well on them.” Ms. Clamborg smiled at that, which was infinitely better than the sheer terror writ there just moments before. She sat taller in her seat.

“The ambient air temperature, pressure, pH and humidity, the liquid score and the angle of the head.”

“Excellent! Why do they all have different subequations in the progression?”

“Excuse me?”

“In the subequations. All the little bits surrounding the variables. Why are they all different?”

“Oh. Because they’re weighted differently.”

“Yes, but why?” Miss Clamborg looked as if she might actually cry instead of answer. Rebekka swiped the equation away and began writing again. “Why can we not just create a linear composite of the component variables?” Rebekka wrote again.

“They all have different metrics,” came an answer from the middle back. Rebekka checked her chart: John Moore. “Yes, Mr. Moore. But what does that mean?” Mr. Moore looked as if she’d asked him to remove an arm instead of explain himself.

“If we used a linear composite, tests with larger integer products would be weighted more in the average,” said another student.

“Yes. In what way?” prodded Rebekka.

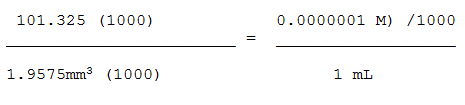

“Well, ambient temperature is measured in degrees celsius, with honestly, a range between -17 and 50, while atmospheric pressure is measured in kiloPascals and is usually between 98.21 and 104.98, but pH is a base-10 logarithmic factor of active hydrogen ion concentration in moles per liter, which ends up being a number between 0 and 14. Shall I go on?”

“Please do.” Rebekka glanced down at the seating chart: Robert Hamm. Either he was trying to sound smart or he actually was. She checked his scores: he actually was, which he then continued to prove:

“Humidity, which is expressed as relative humidity in the equation, measures the current water content of air at a given temperature, relative to the maximum for a given temperature, in grams per cubic meter, and is expressed as a percent which can, therefore, be anywhere from 0 to 100, while a liquid score can reasonably be upwards of 100 if it’s not 0, and head angle, which is essentially the positive representation of a degrees coordinate difference, can be anywhere from 0 to 180.”

“So pardon me while I play uneducated devil’s advocate,” she said as an aside, then, “They’re all numbers. Why can’t we just add them up and divide by 6?”

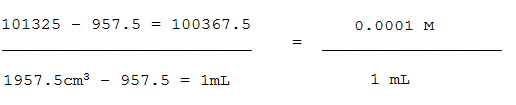

“Because millimeters of mercury is not the same as a log of moles per liter. If we just added the numbers, the most important contributor to the average would be atmospheric pressure. Its average measure is over 1500% the average pH, but a pH of 14 has a much greater impact on the degradation of a body than even a below normal atmospheric pressure.”

“Aha!” Rebekka shouted. A quiet chuckle rolled through the room. “So we need to increase the importance of pH in relation to atmospheric pressure.” She returned to her slate and expanded the equation across the display.

“So what could we do to make atmospheric pressure and pH equal to one another?”

“But they aren’t equal to one another. pH is more important.”

“Baby steps, Mr. Hamm. And I’d appreciate if someone else would jump in here. Not that I don’t appreciate Mr. Hamm’s input, but this is a class, not a conversation.” No one offered to join. Rebecca checked her podium display again. “How about… Mr. Wallace.”

Rebekka looked up to the matching station and found a thin, unassuming young man, slunk down in his seat as Oliver had been, unable to hide a look of stern concentration behind a pair of large, thick glasses, staring fixedly at his personal display. He had not acknowledged, in any way, her calling on him. She quickly checked his scores from the seconds, worried that she was about to humiliate some meager student: top of the class. Thank goodness, she thought. She hated nothing more than embarrassing a struggling student. “Mr. Wallace?” she asked, since he still had not acknowledged her.

“Yes, yes,” he answered, almost impatiently, and pushed his glasses up his nose. He still did not look at her. She caught several students around him rolling their eyes or settling back into their seats in resignation and decided this was not an unusual social presentation for the young man. Rather than pursue an interaction that was obviously difficult for him, she pressed on.

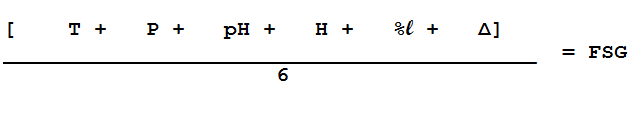

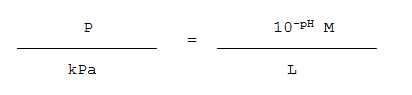

“What equation could we set up to make the measures of pressure and pH equal to one another?” She highlighted Mr. Wallace’s station on the chart and pressed a button. “Your slate is active.”

Mr. Wallace’s larynx very deliberately slid up and down his neck and he sat up straighter in his seat. He leaned forward and squinted at his display, as if those very thick glasses weren’t quite up to the task of bringing it, just 2 feet from his nose as it was, into focus. Finally, he wrote on his slate. It was reproduced on the main display:

Then he shifted in his seat, thought just a moment, and began adding to it:

“Very good, Mr. Wallace!” she gasped, quite surprised at the speed with which he’d managed the problem. There was an audible sigh in the room as if 50 people let out a breath they had been holding. Mr. Wallace immediately slunk back down into his seat. “Really excellent work!” she added, but praise did not seem to have the same effect on Mr. Wallace as it had on Ms. Clamborg. Mr. Wallace seemed even more nervous now. His stern concentration had deepened and she thought, perhaps, it was less that than an increasing embarrassment at being called attention to. So he shines when he’s doing, not talking, she thought. “Can you solve it for us?” He gave her a curt nod and leaned forward again. Finally, he looked at her and his face formed a question, albeit a stern one (His brows seemed permanently knit together.) She realized he was looking for input. “Oh. Use the averages for each.” He nodded again and returned his attention to his slate.

Then

“But that doesn’t get us anywhere!” said Mr. Hamm, obviously exasperated.

“It proves it can be done. And very nicely, too, I might add, Mr. Wallace,” Rebekka replied. She was simply unable to not praise the young man for the elegance of his figuring, despite knowing it would cause him some amount of consternation.

“Yes, but we’re no closer to actually weighting the measures!” Mr. Hamm huffed. He performed a rather restrained version of throwing his hands up.

“Well, I suppose that’s true,” Rebekka conceded, taking the slate back from Mr. Wallace. She quickly highlighted the work on the display and saved a copy to a new pin (she wanted to share it with Ibe later) before tucking the work in the upper right corner of the display. “Perhaps practically, you are correct, but theoretically? We are getting so very close.”

At the mention of that word ‘theoretically,’ Mr. Hamm seemed to have some sort of revelation. It crossed his face as a slowly appearing shock first and then morphed into a sort of wonderment, mixed and fighting with not a small amount of contrition. A glance around the room at shining eyes and forward postures told Rebekka that many other students had glommed on to the significance of that word – and what she was doing with it - as well. Murmurs welled then quickly died, darting around the room, waxing then waning, as glommed students explained to un-glommed neighbors, and more and more faces presented that same wonderment, attention supplanting Mr. Hamm’s discomfiture. Rebekka smiled. No one ever said Processing students were dumb.

“Mr. Wallace? I used Torrs, but I think I like your way better. And Mr. Hamm? While I appreciate that you’ve obviously done your homework, I’m sure you’ll appreciate that, for what I’m doing here, you are jumping ahead, yes?” His color deepened and he nodded.

Rebekka returned to her slate and swept all but the upper right clean. “We were very far away practically.” She began to write out equations, giving each its own little area of the display. “But remember, this was new territory; there were no precedents. We didn’t have anyone’s work to build on. It was really and truly theory. Sure, the maths existed, but no one had tried anything like what we were proposing, so no one had ever tried to take advantage of this particular correlation between them. No one had tried to combine them as we were. Figuring this out was monumental. And it took the time that it took. And Ibrahim – your Dr. Heinemann – was instrumental in determining the inclusions we needed to figure. You all should be very happy with the professor you have for this class; he literally thought this stuff up.” A sprinkle of chuckles and conversations answered her and quickly died as she continued.

“So we’ve proved we can equalize, but – as Mr. Hamm pointed out for us – do we want to?” She returned to her slate and the first equation she’d written. She began to solve it, writing out the steps below it, until she had her answer – over milliliters - and moved on the next. “Mr. Wallace equalized to milliliters, and with some more of that excellent figuring, I’ve no doubt he would figure out how to get them all there, since most of the measures are, at some point, a comparison to volume.” She continued solving until she reached the last equation. “The real bugaboos, are temperature and angle.” She held up a hand to stay any student bold enough to jump in at this point, though she didn’t think it likely, since she’d pretty well squelched Mr. Hamm. “I know, I know. The Koenig Series could find for the opposing volumes of a sphere bisected by the slope of the angle’s plane…” She solved the right side of the equation. “But once we had those volumes, the question became whether that would really equal the measure we were trying to express with the angle.” She leaned in toward the class and, hand up to her mouth as if she was sharing some great secret, she mock-whispered “It doesn’t.” Titters filled the room. “And then there was temperature. It defied adjustment to volume.” She tapped her slate several times, thinking, before wiping the slate clean.

There were audible gasps. Several students actually cried out. Several jumped to their feet, as if they could rush the stage and stop the wipe, now an ever growing number of microseconds complete. She even heard one sob. Rebekka was a bit surprised by the reaction. “These are not the equations you are looking for, you know.”

She began to write again. “These are the ones you want.” The class quickly fell silent as everyone began industriously copying her work to their own slates. “Keep in mind, these original subequations have had to be altered as advances in nanocryonics have occurred, so you’ll find several have been altered in your text. Originally, our TSE window was measured in hours. We actually planned to have the Extraction Apparatus mobile, with Inclusion calculations done in transit, so we could scan on site and not waste valuable cryo time.”

#################

Waters flowed the market, letting the currents of people carry him along, trying to think.

That wasn’t true. He was trying to think of only one thing, and other things kept getting in the way. He’d already made the trip from in to out and back again, and when his feet hit the wood of the docks once more, he slipped from the stream, climbed the pilings to a precarious height and looked back, now high enough to watch the streams flow towards and away, eddying near the stalls, swirling a whirlpool where they met in the middle. He tried to get lost in their movement as he’d been unable to do within them. That didn’t work, either. The screeching of the fishwives still hawking despite the late hour, and the shouting and laughter of the rousters as they carried away the dregs of the day’s catch from those stalls that had the sense to be closing, kept pulling his mind back. Also, it seemed it didn’t matter which stream he followed, whether he was here Seaside, where the salt and the smell of fish in the air was a palpable thing, or there at the Edge, where the pointed not-stares of his people were just as palpable: the MIN was always in view. And that brought thoughts of the girl.

Still, here or there was better than Boma right now. He just couldn’t be so near Umbriel anymore, watching her go about her normal day, uncaring of the urgency, when he knew -– he knew! -– they should be searching. Right Now. Before her light found and joined. Then she’d be just some baby, and it would be another decade at least before they could begin to hope again.

He’d finally just slipped and came back to the city. Perhaps not the best choice if one was trying to not think of the girl, but more importantly it was not Boma, where Umbriel’s nonchalance and ignorance chafed him so.

Waters had no illusions: he would not live to start the search again in ten years. Neither would Umbriel, likely. She was old, too. Oh, she might not look it, thanks to the Adoel, but she was his age. She’d grown up with him and Willow. And the Adoel couldn’t keep her going forever.

Then who would be their Umbriel? Mishka? He was not impressed with that acolyte. She did not have the force of personality required to be the Umbriel, and while that might appeal to his manipulative nature, who even knew if she really had the gift? What good would a new Umbriel be if they couldn’t actually hear the Adoel?

No. It had to be now. They had to find her light now. And he couldn’t do it alone. It was hard enough finding latent Ahera (and he was good at his job. The best Malakamawti in generations. Everyone said so), but to find one single light in a hundred million lights? With the naked eye? Never mind its unique color. Darker was harder to see, after all. And it could be anywhere. He needed the Adoel. Which meant he needed the Umbriel.

And she was being her stubborn, stingy self. Again. Did she never learn? She always gave in eventually. But eventually was too long this time.

And this time, he knew he was right. He just knew it. And so should Umbriel, honestly. She’d read her. She had to know it, too!

Frustrated, Waters climbed off the pilings and dove back into the stream of people heading inland, letting the current move him, as he had so many times already today. He would worry about the Umbriel when he reached the den.

##################

“It was my string,” Rebekka announced as she swept through the doorway, waving the printouts in her hands. Her excitement was palpable. She’d found the answer. Still, he played along. Let her announce it in her own way. Let him bask in the light of her enthusiasm a little while longer.

“Ridiculous. Not like you just popped this off the top of your head, Bekka. We’ve got the simulations to prove it’s a perfectly sound theory.”

“That’s just it!” She nearly jumped to grab his arm, lustrous curls dancing about her shoulders and jawline. She absently brushed a wayward lock from her eyebrow only to have it fall again near her beautiful, bowed lips. “It was too perfect!” He loved her like this. So animated. So passionate. He so wanted to kiss those lips. “The series was looking for perfect matches to the known models. It was the raw data that gave it away.” She moved away from him to spread the data sheet across the workbench, not caring what she covered or knocked over. Pens sprawled and dribbled from the edge, bouncing against the stone with a clatter. She paid them no heed as she searched and finally pointed at a line of code on the sheet. “I saw patterns within the sets that the string wasn’t picking up because it was looking at the whole shift and trying to find one model, when, in fact, each shift contains several models. Duh.” She searched his eyes for understanding, and he felt a sudden pang of guilt at his preoccupation with the curve of her neck where it met her labcoat collar. She continued undisturbed. “The series was coded to find only perfect matches and boot anything that wasn’t. Completely my fault. Even ToD searches for multiple patterns. I just didn’t think of it when I wrote the code. So stupid, really.” She waved her hand and Ibe caught himself following her lithe fingers as they danced through the air. “I sequenced a simulation for minimum required fraction, just like ToD. Match, remove, compare again. Multiple passes at each set. You should see the depth, Ibrahim!” She touched his arm again, and he felt electric. He toyed briefly with grabbing her right there and laying her out on the data sheets, but he knew she was too intent on her discovery to accept his advance.

“So shall we run her through again?”

Rebekka nodded. Her hair danced again, shimmering in the lights of the lab. God, she was beautiful.

Andrea L Boyd

Andrea L Boyd