A Performance-Based Capital Structure to Raise Venture Capital Via an Initial Public Offering (IPO)

Introduction

The first chapter of The Fairshare Model is presented here to entice you, Dear Reader, to pre-order a copy of the book. If 750 people order a copy, Inkshares will commit resources to edit and publish the book. Those who pre-order will receive both an e-book and a signed first edition printed book.

All aspects of your order will be managed by Inkshares. Once the order threshold is reached, it will take approximately six months for the book to be published.

All eighteen chapters written so far are at www.fairsharemodel.com. I plan a few more. The published version will be edited and updated for rules on equity crowdfunding that go into effect May 2016.

Place your order and you will hasten publication of The Fairshare Model with no risk! There is no risk because the draft is nearly complete and you can read it, plus, you either get the book (e-book and signed first edition) or your money back.

Karl M. Sjogren

Chapter 1: The Fairshare Model

Preview

- Foreword

- Purpose of this book

- Audience

- Why I focus on valuation

- Encouragement and a compass

- Vision

- Goal

- Problem

- The Fairshare Model

- Chicken vs. Egg

- Thesis

- A Bird’s Eye View of the thesis

- Onward

Foreword

This chapter addresses the context for the Fairshare Model and describes what it is.

Purpose of this book

The purpose of this book is to spark broad discussion about how to re-imagine capitalism at the DNA level. A capital structure is a company’s DNA—it defines ownership interests and voting rights—so everything that capitalism is (or can be) flows from the expression of qualities that originates in its capital structure.

The Fairshare Model is an idea for a performance-based capital structure for companies that raise venture capital via a public offering. Its mission is to balance and align the interests of investors and employees; to offer public investors a deal comparable to what venture capitalists get.

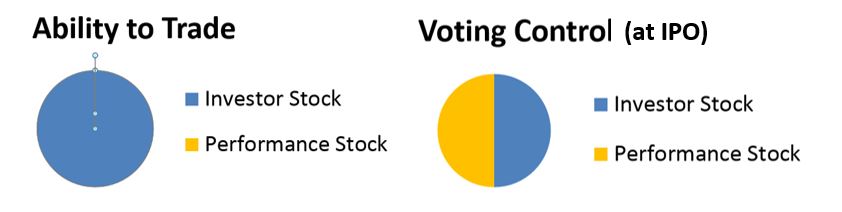

It has two classes of stock. One trades, the other cannot; both vote. Investors get the tradable stock, which is called “Investor Stock.” For past performance, employees get it too. For future performance, employees get the non-tradable stock, which is called “Performance Stock.” Based on milestones, Performance Stock converts into Investor Stock. The model’s structure is simple; its complexity flows from a philosophical question, “what is performance?” How that question is answered will vary—it can be whatever a company’s shareholders say it will be.

The idea behind the Fairshare Model is simultaneously radical and ordinary.

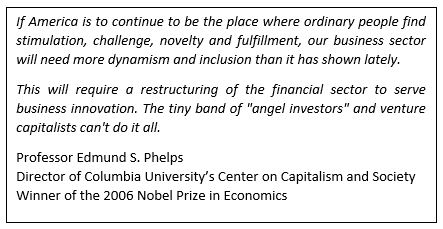

It is radical because the model presents a very different philosophy about how to structure ownership interests in public companies whose value chiefly comes from their uncertain promise of future performance. Such companies have raised venture capital for decades via Wall Street initial public offerings and recent changes in securities law will accelerate such activity. Another way the Fairshare Model is a radical idea is that it presents a way for Middle Class investors to participate in venture capital investing on terms comparable to what venture capitalists get.

The Fairshare Model is ordinary because it encourages the public capital markets to work the way most markets work, where sellers compete for buyers by offering a better deal (i.e., lower prices and better terms). Remarkably, this isn’t common with a conventional capital structure; companies don’t compete for public investors by offering lower valuations and better protections.

This reflects weak market forces that exists because IPO issuers and Wall Street firms don’t want to compete on terms and because many public investors are not valuation savvy; they are unsure what valuation is, how to calculate it and how to evaluate one. Oftentimes, “market forces” is a phrase used to explain adverse developments for the Middle Class, but they can bring better deals to average investors. One way to re-imagine capitalism is with stronger market forces that result in a better product and increased competition for public capital. The Fairshare Model promotes this in a win-win manner—with significant benefits for investors and employees.

So, how does one go about changing the DNA of capitalism? By popularizing a new philosophy about the relationship between companies and their IPO investors. The key idea? Treat public venture capital like private venture capital. That is, provide IPO investors price protection, comparable to what venture capital firms get in a private offering, then, reward well-performing entrepreneurial teams with more ownership than they would get in a private offering to a venture capital firm.

I hope you’ll discuss the Fairshare Model with others. Generating interest—“buzz” among hives of people with interest in entrepreneurial companies—is the job of this book. As the model’s philosophy gains traction, all manner of experts will evaluate how to implement it for different types of companies; that will only happen if there is clear investor interest in the model. Then, some companies will try it!

Think of this process like baking the sourdough bread that the San Francisco Bay area is renowned for. This book will serve as the “starter,” the yeast culture that gives the bread its unique flavor and texture. Readers like you will contribute ingredients to make a dough, but instead of flour and water, you will provide ideas and enthusiasm. Experts in various matters—law, tax, accounting, organizational development and others—will knead it. Once this dough rises, early adopters will try it. The aroma of a fresh approach to capital formation will attract more people to the kitchen who contribute more ideas on what to make.

Often, after I’m exposed to a new idea I see other things in a new light. I get pleasure when this happens—I view it as a reward of being curious. I trust that you feel similarly, Dear Reader. I seek to engage you in new thinking about capital markets, an interplay between concept and possibility, analysis and imagination. And I hope you’ll similarly engage others who will, in turn, do the same. So, let’s begin to explore how to re-imagine capital formation, the DNA of capitalism!

Audience

First and foremost, this is a book for thinkers; practical minded people who like big ideas.

My principal target audience is comprised of investors who might want to invest in a start-up company someday. Some of them see a problem—such companies are notoriously difficult to value. For them, the Fairshare Model is a solution because it avoids the need to value undelivered performance.

My secondary target audience is comprised of entrepreneurs who are willing to consider a public offering as an alternative to a VC round.

There is another audience that is important, but my attention isn’t focused on them now. It is attorneys, accountants, investment bankers and portals, stock exchanges and others involved in the emerging company ecosystem. Their involvement is needed to help implement the Fairshare Model.

Broadly, this book will appeal to those who are interested in the following:

- Economic philosophy and behavioral finance

- Valuation theory (in an easy to understand manner)

- Corporate governance and organizational behavior;

- How to align the interests of investors and employees;

- The intersection of social investing and capital markets;

- Economic growth and a partial solution to income inequality that does not rely on taxes.

Why I focus on valuation

I emphasize the importance of valuation for public investors. A Wall Street Journal article succinctly states why buy-in valuation deserves to be emphasized. [Bold added for emphasis]

An enormous body of academic research has proved time and again that your long-term investment returns will overwhelmingly depend upon just two things: asset allocation—how you spread your money between investments like stocks and bonds—and the value of those investments when you buy them.

Dear Reader, have you noticed news stories that mention valuation? They are far more common than a decade ago. Do you puzzle over the amounts and wonder how to evaluate them? Do you know the difference between pre- and post money valuation? Subsequent chapters discuss valuation concepts in a manner that anyone can understand. You will learn how to calculate a company’s valuation, how venture capitalists evaluate one and how they protect themselves from investing at too high a valuation.

Questions about valuation are about to bloom as a result of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act of 2012, also known as the JOBS Act. It led to changes to securities regulations that makes it less expensive and difficult for young companies to sell stock to public investors.

Encouragement and a compass

There may be times when points that I make are unclear to readers who are unfamiliar with capital structures. Dear Reader, I offer two things to deal with moments when you feel disoriented.

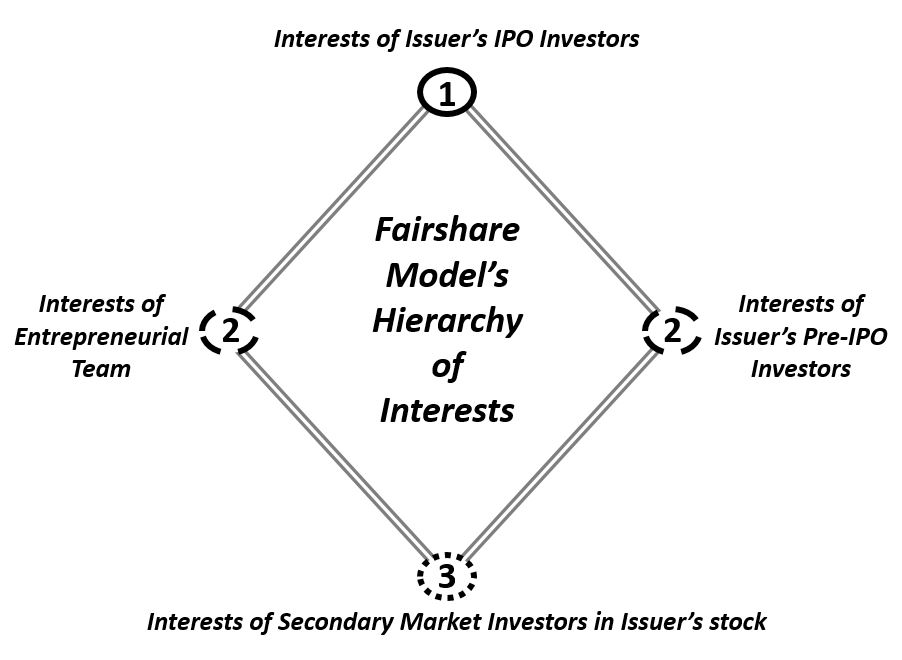

The second thing that I offer you is a conceptual compass. With respect to how capital formation works, between where we are now and where I imagine we can be, is unexplored terrain. When you wonder where I am headed, where I will turn, how I think a matter should be settled, look to my compass. On it, True North is the interests of public investors who buy stock from a venture-stage company in an IPO. The interests of entrepreneurs, private investors and investors in the secondary market are important, but not as central as those of IPO investors; there is only one True North.

The second thing that I offer you is a conceptual compass. With respect to how capital formation works, between where we are now and where I imagine we can be, is unexplored terrain. When you wonder where I am headed, where I will turn, how I think a matter should be settled, look to my compass. On it, True North is the interests of public investors who buy stock from a venture-stage company in an IPO. The interests of entrepreneurs, private investors and investors in the secondary market are important, but not as central as those of IPO investors; there is only one True North.

Public IPO investors occupy that position for the Fairshare Model because if they make money, there will be more money for entrepreneurs and their private investors.

In the Fairshare Model’s hierarchy of interests—IPO investors are at the top. So, the answer to any question about how to make the Fairshare Model work will likely be found by asking “What is best for the IPO investors?” while giving due consideration to the interests of the other key constituencies.

This ranking hierarchy is diagrammed below. The interests of IPO investors is at the top, in the #1 spot. The interests of the entrepreneurial team and the interests of pre-IPO investors (i.e., angels) are tied at the #2 spot. The interests of secondary market investors occupy the #3 spot.

Vision

My vision for the Fairshare Model is that average investors will be able to make venture capital investments…on terms comparable to those that professional investors get.

Goal

My goal is a deal structure that will:

- Expand entrepreneur access to capital.

- Offer liquidity to wealthy angel investors who support private companies.

- Create an attractive yet prudent option for average investors to be “mini angel” investors.

Note the self-renewing cycle. Entrepreneurs are more likely to attract capital if investors feel fairly treated for the risks they assume. Angel investors are more likely to invest when they believe it can attract investors to the next round of capital, and, there is the prospect of liquidity (the ability to sell shares). Public investors are more likely to provide that capital and liquidity if they, too, feel fairly treated.

Note the self-renewing cycle. Entrepreneurs are more likely to attract capital if investors feel fairly treated for the risks they assume. Angel investors are more likely to invest when they believe it can attract investors to the next round of capital, and, there is the prospect of liquidity (the ability to sell shares). Public investors are more likely to provide that capital and liquidity if they, too, feel fairly treated.

Within a generation, I hope that the Fairshare Model will be seen as a viable and attractive approach for companies that raise venture capital in a public offering. This will happen if it helps them raise capital and provides competitive advantage in attracting employees and managing them.

Problem

A conventional capital structure is a weak model for a self-renewing cycle of capital because it has a fundamental problem—a need to set a value on future performance anytime equity capital is raised. This is hard to do in a reliable manner, but a conventional model demands that be done.

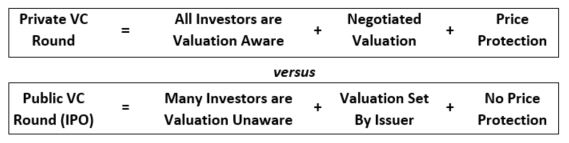

There is a work-around to this problem in a private venture capital offering; valuation-savvy investors negotiate a valuation and price protection. But there is no work-around in an IPO, which is increasingly used to raise a round of venture capital. So, public investors have a problem—many of them are valuation unaware, the valuation is set by the issuer, and they have no price protection even though they assume significant risks. These conceptual formulas show the problem.

Before public investors can solve their problem, they must first realize that they have one—that they are treated relatively poorly. Then, they need to support ways to solve it. The Fairshare Model is one such solution because it provides a VC-like deal structure for IPO investors; it treats them fairly.

The Fairshare Model

The Fairshare Model is for a company (an “issuer” of securities) that raises venture capital via a public offering. There are two classes of stock. One can trade, the other cannot; both can vote.

I refer to the tradable stock as Investor Stock; it is sold to investors to raise equity capital for the company. From a legal perspective, Investor Stock is common stock.

I refer to the non-tradable stock as Performance Stock; it is issued to employees, consultants, directors and others. From a legal perspective, Performance Stock is preferred stock.

Investor Stock always has at least 50% of the voting power, even when it represents less than 50% of the total shares issued.

At the IPO, there is far more Performance Stock than Investor Stock, perhaps ten times more, enough to envision years of future performance but, as a class, Investor Stock has at least half the voting power. So, even if Performance Stock is 80 percent of total shares and Investor Stock is 20 percent, Investor Stock has 50 percent of the voting power. However, when Performance Stock represents less than 50 percent of total shares, voting is based on an issued shares, not class. Therefore, if Performance Stock represents 40 percent of total shares, it has 40 percent of the vote and Investor Stock has 60 percent.

Based on performance milestones agreed to by the two classes of stock, Performance Stock converts to Investor Stock. There will be variation in how performance is defined and measured based on:

- Industry; software, manufacturing, services, biotech, etc.

- Stage of development; pre-revenue, early growth, late growth, mature, etc.

- Corporate purpose; a socially conscious issuer may have non-traditional goals.

- Geography; countries and regions may favor certain approaches.

- Personalities of the entrepreneurial team and their investors.

The performance criteria is in the issuer’s incorporation document and offering document (i.e., prospectus, registration statement). It may be modified by agreement of both classes of stock.

Ordinarily, an offer to acquire the company must be approved by both classes of stock. Such an event may cause a very significant conversion of Performance Stock.

Chicken vs. Egg

No company has used the Fairshare Model. It’s entirely conceptual. I have no anecdotes about how it has actually worked.

What I can tell you is that about fifteen years ago, in 1997, I co-founded a company called Fairshare that promoted the Fairshare Model and a plan to implement it. We had some success (e.g., a robust educational website, 16,000 op-in members) before we slipped under the waves in 2001, in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts.

I touch on my Fairshare adventure in later chapters. One lesson that I learned is how to address the Chicken vs. Egg conundrum. Companies will adopt a new capital structure if there is an audience for it. Investors want to see companies using it before they get enthusiastic about it. The movie “Field of Dreams” has a line to describe to such a challenge, “If you build it and they will come.” In our case, was the “it” an opportunity to invest in a specific company that used the Fairshare Model? Or, was “it” an audience of investors interested in the Fairshare Model? Which comes first?

For a couple of reasons, we decided that the latter approach, build the audience, was the most practical. The most important one was that companies we wanted to attract could raise capital in other ways. There would be no reason for them to craft an offering using our novel structure before there were investors who liked it. Also, garnering support for an idea before it is implemented has an advantage. When a particular implementation represents an idea, attention is directed to its specific attributes and away from the idea. All companies have shortcomings so having some become the “poster child” for the Fairshare Model risked making their flaws the focal point, not the Big Idea. This issue come up in politics. It is why politicians prefer to campaign on a Big Idea rather than on a specific proposal (i.e., “I’m for a balanced budget” vs. “I want to cut these programs or raise these taxes”).

Some suggested another option—persuade venture capitalists and investment bankers to support the Fairshare Model. Well, that would be greeted with the interest that a high end retailer has for a competing discount store. In fact, in the late 1990s I pitched the Fairshare concept to a prominent San Francisco based VC who was well known as a political liberal. His response was...

“Why would I be interested in THAT?”

Much has changed since then but not that sentiment, I’m sure. However, fast forward a half dozen years or so from now. Once the model’s effectiveness is demonstrated, a new breed of VC is likely to consider using it. Perhaps, it will be to fund a new round for a portfolio company that is a single or double in baseball-speak, not a triple or home run. A boutique VC fund might use a Fairshare Model IPO to bring in public investors to co-invest. This would limit the amount of capital the VC needs to raise, allow early customers to have a piece of the action, and provide liquidity for the fund’s limited partners. There is similar potential for new style of broker-dealer to create a niche market in investment banking using the Fairshare Model.

For such things to happen, VCs and broker-dealers need to see that there is a market for the model, and, that there is money to be made. This will take time and experience, but it will happen, I’m certain, because of the problem that exists when applying a conventional capital structure to a start-up. As public investors become savvier, many will have interest in a better deal.So, I lead with an idea because it’s all I’ve got. If enough people visualize the egg, intrepid (not-so-chicken) entrepreneurs will give it a go. A community of experts will grow to help other companies figure out how to make the Fairshare Model work for them. Supportive infrastructure will develop. A self-sustaining community of integrated interests will form…organically, if you will.

How many people are needed to give the Fairshare Model the traction that it needs? Half of a small fraction of those who supported the Occupy Wall Street protests. There were enough of them to attract wide attention to their dissatisfaction with The-Way-Things-Are. It doesn’t take many to spark a revolution—the Boston Tea Party wasn’t large either.

When protesters demonstrate (it doesn’t matter why), they channel Howard Beale, the fictional television news anchor in the 1976 movie, Network. One night Beale snaps. He’s enraged that his network is abandoning “hard news” for programming that generates high ratings. On a live broadcast, he exhorts his audience to stop being mere observers of the problems that define their existence. In part, he says:

"So I want you to get up now.

I want all of you to get up out of your chairs.

I want you to get up right now and go to the window.

Open it, and stick your head out, and yell, ’I’M AS MAD AS HELL, AND I’M NOT GOING TO TAKE THIS ANYMORE!’

I want you to get up right now, sit up, go to your windows, open them and stick your head out and yell - ’I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!’

Things have got to change. But first, you’ve gotta get mad!

You’ve got to say, ’I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!’

Beale’s speech expresses anger and frustration…negative energy. It mobilizes, which is why political campaigns favor negative ads. Ironically, though, negative energy is the opposite of what is needed to turn things around. To build something better, one requires positive energy—optimism, creativity and cooperation.

I rely on positive energy to solve my chicken and egg puzzle.

How many people might have to express interest in the Fairshare Model to get it on the proving grounds? My guess is 20,000, but it could be less than 10,000. No big deal. In 2014, a guy raised $55,000 from 7,000 people on Kickstarter to make a potato salad. Google it.

If there is investor interest in the Fairshare Model, some companies will try to raise capital using it. If enough of them have good results, more will come.

Thesis

Average investors lack an attractive, prudent way to invest in young companies. The opportunity to innovate in this space reveals itself when one considers venture capital from the perspective of public investors.

Normally, venture capital is viewed from the perspective of entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, wealthy investors and Wall Street firms. But look at it from the perspective of public investors and it looks interestingly different, like the shift from black and white to color in The Wizard of Oz movie.

Make this shift in perspective and the Fairshare Model is intuitive, even to those who know little about venture capital. Those with knowledge about capital formation will recognize similarities between the Fairshare Model and how VCs construct their deals. Dear Reader, as you contemplate The-Way-Things-Are, a question will form in your mind. Why should public investors who invest in venture stage companies be treated so poorly? Then, another question will arise. What can be done to change this?

The Fairshare Model is an innovation in deal structure that treats IPO investors as venture partners as opposed to inhabitants at the bottom of the capital market food chain. To achieve its goals, it adopts a different approach to IPO valuation. Essentially, it extends the concept of price protection from the private VC market to the public VC market. To extend the Oz metaphor, investors have to see the capital markets “in color” to appreciate this idea, which is what this book will help them to do.

Early stage companies are hard to value because virtually all their value comes from future performance, which is steeped in uncertainty. A conventional capital structure demands that a value be placed on future performance each time new stock is sold. VCs skirt this problem by securing deal terms that retroactively lowers their buy-in valuation if expectations are not met. Public investors don’t get similar protection when they buy shares in a public venture-stage company.

For public investors, the risk of buying stock at an excessive valuation will grow as a result of the JOBS Act of 2012 because more unproven companies will seek capital from them. The risk can be mitigated by improving investor awareness about valuations. This risk can be reduced with the Fairshare Model because it eliminates the need to value undelivered performance.

The Fairshare Model was conceived to solve a micro-economic problem—how to enable public investors to invest on terms comparable to VCs. It incidentally offers ideas on macro-economic challenges such as slow economic growth and rising income inequality. In both a small and large sense, the Fairshare Model re-imagines capitalism. Its challenges rest on human behavior, not technical matters.

For companies, the promise of the Fairshare Model is twofold. First, it will be easier for them to raise money because they can offer investors a better deal than with a conventional capital structure. Second, it will provide them with a competitive advantage when recruiting and managing human capital.

A Bird’s Eye View of the Thesis

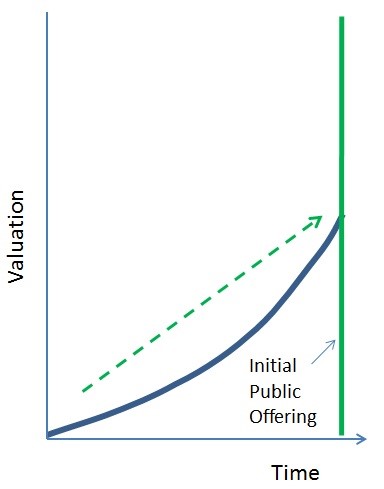

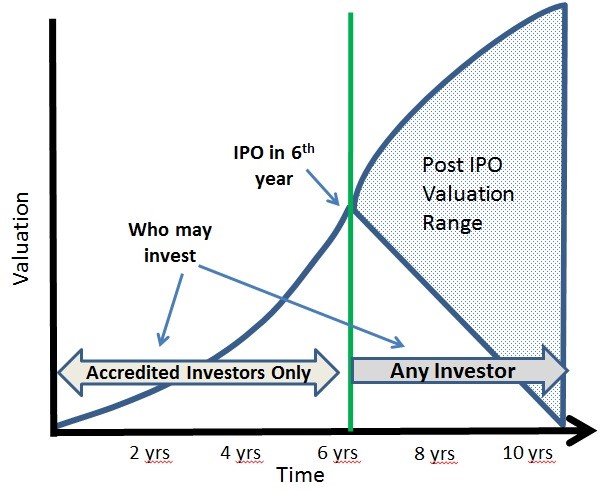

The next few charts illustrate what the valuation curve often looks like for a company that uses a conventional capital structure.

Look at the following chart. What drives the increase in valuation that often occurs as a company approaches its IPO when a conventional capital structure is used?

Is it performance?

Or, is it something else?

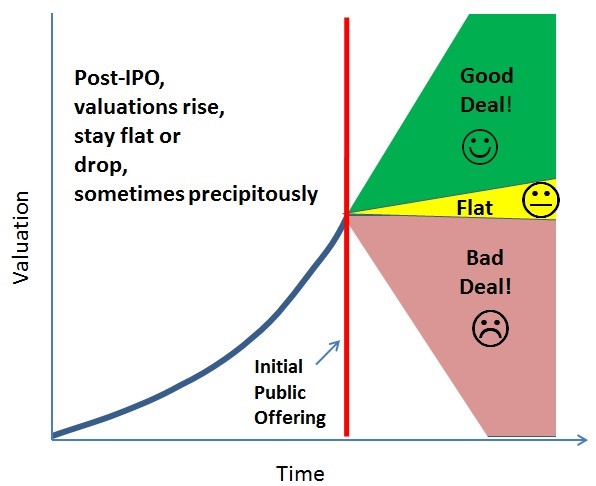

The chart below shows the same timeline but from the perspective of public investors. What are the risks that the IPO valuation presents?

In the chart below, the company has its IPO in its sixth year. However, if it were sooner, the valuation curve would look similar if a conventional capital structure is used. That’s because companies tend to be valued higher when they are public and, so, private companies rise in value as expectations of a public offering heighten.

Note that only investors who are wealthy enough to meet the “accredited investor” standard defined by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission are allowed to invest in a private company; but anyone can invest in a public company

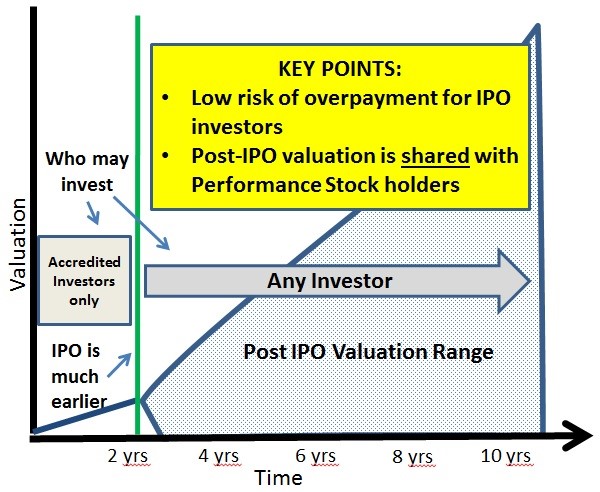

Difference between a Conventional Model and the Fairshare Model The Fairshare Model encourages companies to offer IPO investors a private venture capital valuation. In the chart below, the issuer goes public sooner, in year two, at a much lower valuation. If it performs, the increase in valuation is shared by the investors and employees. If it doesn’t perform, public IPO investors lose less because the valuation was lower.

What is the issuer’s incentive to offer a low IPO valuation? A well-performing team can own more of the company than they would if a VC backed them. Plus, they can be more competitive in attracting and managing human capital.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

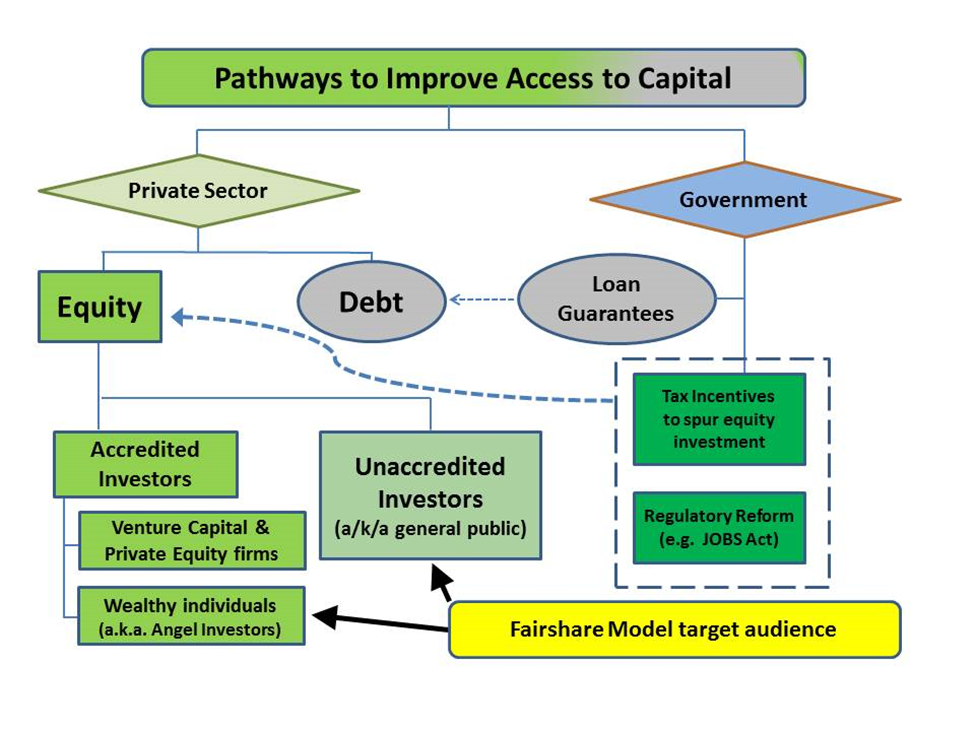

To be clear, the Fairshare Model is for a public offering of equity, one that can be sold to any investor. Its goal is to provide them a deal that is similar to what institutional investors—venture capital and private equity firms—get when they invest via a private offering. The chart below shows that there are two pathways to improve access to capital for companies—the private sector or government.

Government capital is available to a small proportion of companies (e.g., defense, energy, healthcare), often a loan guarantee, not equity. Government can spur the availability of capital via tax incentives and regulatory reform such as those in the JOBS Act.

Most equity capital comes from the private sector via private and public offerings. Only accredited investors (i.e. institutions and wealthy individuals) may invest in a private offering but anyone, including unaccredited or average investors, can invest in a public one. By meeting the requirements to offer stock to anyone, a company becomes “public” even if it is a startup.

A company that issues stock in a public offering (an issuer) can sell shares directly to the public in a direct public offering or hire a broker-dealer to sell them. The Fairshare Model can be used for any public offering—it is not dependent on how the shares are sold—and it’s target audience is individual investors, be they accredited or not.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

What is the macro-economic benefit of the Fairshare Model?

Young companies are the engine of economic growth and job creation—it follows that improving their ability to raise capital should provide social benefits in the form of economic growth, even after considering that the investments face high risk of failure.

The Fairshare Model does not reduce the risk of failure for IPO investors. It reduces the cost of failure when measured by the cost of owning a given percentage of a company.

It is analogous to the casino game of roulette. Imagine that each chip represents a given percentage of ownership in a company. The Fairshare Model does not change the odds that a given bet will pay off, rather, it reduces the cost of each chip. This allows the gambler to place bets on more numbers for the same money. More bets on start-ups could pay off, in a macro-economic sense. The Fairshare Model reduces the cost of a given bet because the investor need not pay for future performance before it is delivered. When it is delivered, it is shared with employees using whatever logic they choose to adopt.

This activity has a less obvious social benefit. Even when ventures fail, they contribute to a risk-taking, innovation-seeking culture. Such a culture is richer, more vibrant and productive in the long run than one that is timid. The national psyche is healthier when it pursues possibilities and accepts failure.

Another benefit of the Fairshare Model is that is a private sector approach to reduce income inequality; it does something without the need to achieve elusive political consensus. It does this by enabling employees to benefit from the wealth they create for investors. Put another way, we live in a time when the return on capital exceeds the return on labor, and, this dynamic is unlikely to change. The model addresses income inequality because it provides a vehicle for the providers of labor to participate in the return on capital generated by their labor.

The Fairshare Model rethinks capitalism, but it needs your interest, Dear Reader, and thousands of others to get off the ground.

Onward

The next chapter is for readers who feel that this subject matter might be difficult to understand.

More chapters are at www.fairsharemodel.com